Billing by the Hour: Effective Training Can Be Rewarding

Some food for thought as we start the new year from our FIRC Presenter, Scott Peters.

Generally, I find that instructors do not effectively “bill” for their time. For some reason, despite the money and time they have spent obtaining their licenses and ratings, they devalue themselves. We all know that most instructors move on for various reasons; equipment, responsibility, and pay cheques being some of the most common. Chief Flight Instructors understand this and generally accept it as long as the work being done meets a certain level of quality. Operators also accept this, and unfortunately, to a degree, take advantage of it.

Of course, there are those who choose instructing as a career, but I am going to focus on the vast majority of instructors that are transient within the aviation industry as a whole. Regardless of the instructor’s future career path, they are professionals and should be compensated for their valuable experience and time spent providing quality flight instruction.

Maybe instructors don’t bill enough because they are trying to be “nice” and perhaps curry favour with the student? Maybe they’re just doing what their instructors have done in the past? Perhaps they view their job as a means to an end and want to do whatever it takes to “move on” as quickly as possible?

The industry has fostered a culture where value and quality are not recognized. However, I have found that if you are providing quality flight instruction, the student will pay for it. And perhaps, I can show that it is possible to consider instructing as a viable career path for those who are passionate about it. More importantly, I’d like to look at the idea that doing a good job can earn you just as much money as pounding out flights as fast as possible.

If you were to look at Figure 1, you will see a scheduling comparison between two flight instructors. One is servicing 5 students while the other is working with 3 students. Both have an 8 hour day with a 30 minute lunch break. Assume that each booking consists of 1 hour of flight time. What conclusion(s) could you possibly make? Which instructor would you like to be?

At first glance, I would think it fair to say that a vast majority of the flight instructor population would like to be in Flight Instructor A’s position. I think the rationale for this is fairly obvious as well…flight instructors want to fly!

As we all know, in the flight training industry the frontline service providers are the flight instructors. They are an integral part of the flight training equation. Without them, no flight training would occur. While many have the intention of using flight instruction as a stepping stone, many abuse this opportunity. We put our own selfish hopes and dreams ahead of those we are supposed to be training and in the end it hurts everyone: the student, the school, the industry, safety, and you.

Looking back at Figure 1 from the standpoint of the instructor and the company, it may appear that Instructor A has the best schedule but I would argue that Instructor B has the better schedule. Instructor B’s schedule is the winning solution for everyone, especially the student.

Instructor A has only 30 minutes to conduct Preparatory Ground Instruction, Pre-Flight Briefing, Administration, Pre-Flight Inspection and Post Flight Briefing.

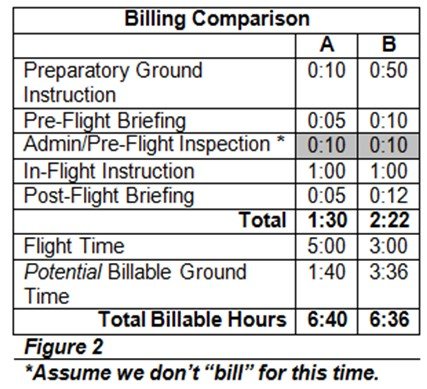

Instructor B has an additional 52 minutes to conduct all “ground” activities. A potential break-down is in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Referring to Figure 3 and assuming 200 days of “flyable” weather in a year and an average instructor wage of $30/hr. you will see that despite a similar annual “salary,” there is a large difference in logged hours. So far, it doesn’t look like much of an argument for Instructor B.My issues with Instructor A however are many, including:

How can he maintain such a heavy daily load/schedule without running behind?

If he does run behind, how will he make up for lost time? Does he cancel later bookings and/or leave out or minimize the already marginalized ground elements? Remember that CAR 405.31 REQUIRES preparatory ground instruction and pre-flight briefings.

By conducting abbreviated briefings, how prepared is the student? How does this lack of preparation translate to in-flight instructional success?

How does this lack-luster approach to flight training affect the student’s skill and knowledge, not only for “today’s” flight lesson but also for future lessons? More importantly, how will this affect them once they are licensed?

Will the student progress and if so, will they complete their training in an efficient, timely, and cost-effective manner?

Figure 3.

In the above example, I would suspect that Instructor A would not charge for any ground time because what he is conducting really has little value to it; thus decreasing the salary I calculated above. Furthermore, based on the outlined reasons, I would expect a high student attrition rate with Instructor A. This would not only affect their reputation, it would ultimately affect future student loads, and hence affect their annual flying hours and salary (and now the company is not too happy either).In the case of Instructor B, despite the lower number of hours they are entering in their logbook, I see numerous “pros” including:

They would have a smaller, less stressful and more manageable student base.

They would have the ability to cater to those students more regularly, allowing for less backtracking and review.

The students will be better prepared and more motivated, resulting in a larger number of students completing their training with better results.

The instructor develops an excellent reputation which translates into a steady flow of students and greater income.

The school is making similar money early on in both scenarios, but with a better reputation and work environment with Instructor B, it can be maintained longer-term.

The “increased cost” to the student for ground briefing will be averaged out by reduced total flight time to licensing; due to proper preparation on the ground.

By adopting a more quality based and student centered philosophy of training, we not only improve the quality and safety of newly licensed pilots, but can see flight training as a potentially more viable career and lifestyle choice for instructors. Even if that is not the goal, we have students that are being properly served by their instructor – and the instructor may even make a reasonable amount of income doing it.

Scott Peters is an ATP Class 1 Flight Instructor, Pilot Examiner, and Instructor Refresher Course Presenter. In his nearly 25 years as an instructor, he has held numerous training positions including Chief Flight Instructor and is presently the Manager of Training at a Canadian air carrier.